One woman’s battle to bring legal literacy – and justice – to survivors of sexual assault

Posted on

When Australian National University graduate Sarah Rosenberg was violently sexually assaulted and choked into unconsciousness by a man she met on Bumble, she knew immediately she needed to report to the police.

But she had no idea her report, and the process of taking the alleged crime through the NSW court system, would strip her of her agency just as much as the violent sexual attack.

And while her attacker agreed to plead guilty to intentional choking and suffocation, the Director of Public Prosecutions insisted on taking a rape case to court regardless of Sarah’s wishes.

After a three-year legal battle, her attacker was found not guilty, as a trial scheduled for one month collapsed within seven days.

Sarah considers herself lucky to be alive today after enduring the mental anguish, not only of the attack, but of the battle to seek justice.

Almost every step of the legal process worked against her, despite her own high levels of education and her mother being a lawyer.

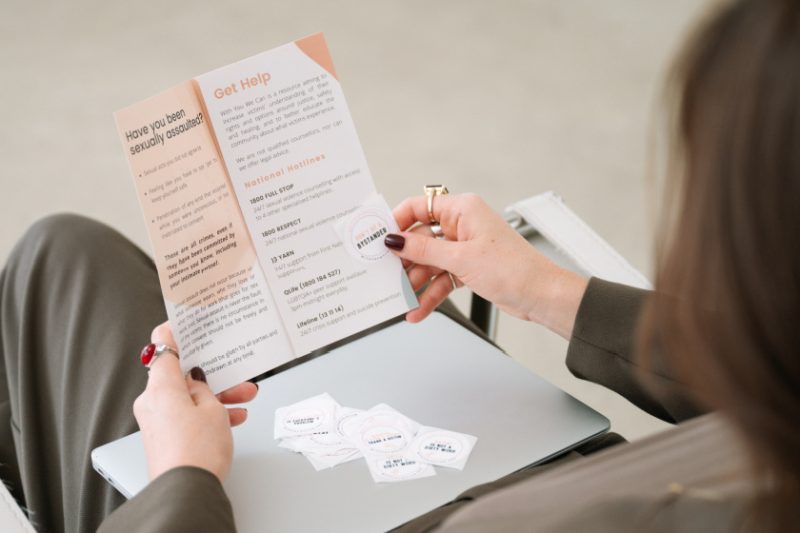

But instead of remaining a “victim”, Sarah has used her own experience to pave a new way forward for those entering the sexual assault justice system, setting up an advocacy group and legal resource With You We Can that demystifies the police and legal processes for victims of sexual violence.

Today With You We Can has issued a call for major reform of the system, using national data to highlight failures of the justice system which lead to most sexual assault victims in Australia entering the system without legal protection, without legal knowledge, and without any understanding of the process they are stepping into.

The white paper What No One Told Us shows that, despite growing public awareness of sexual assault, there is a direct link between low levels of legal literacy and poor justice outcomes for victim-survivors. With 92 per cent of sexual assaults never reported and fewer than one in 10 victims ever receiving legal advice, the report contends that legal illiteracy leaves Australians unprepared for, and unprotected within, the justice system. This gap in knowledge and access is even more pronounced for First Nations women, LGBTQIA+ people, older women, migrant women and people with disability, who face additional barriers, systemic exclusion and discrimination from the outset.

The result is that victims are retraumatised, justice is denied, and public trust in the system continues to erode.

In Sarah’s case, there was a litany of mistakes, traumatising processes and miscarriages of justice which began with her having to go through three different Sydney police stations to finalise a statement, and in which the case was cycled through three solicitors and two Crown Prosecutors as her private counselling records were unlawfully accessed. The trial of her perpetrator went ahead with a 15-minute warning that she was required to be present for questioning and which, after a harried race to court, left Sarah enduring an “out of body experience”.

“I did everything a person could do ‘right’. I reported, I cooperated, I trusted the system,” said Sarah. “But the kinds of heads up you’d think were common decency just didn’t seem to apply.”

Sarah became hyper-aware of the lack of legal knowledge that everyday Australians are taught through this experience. “Most people still think the prosecutor is your lawyer. But you’re not a party to the case, you’re a witness. That means no legal protection, no say in how your story is told, and no one in the room whose job it is to look after you.”

The report calls for three urgent reforms:

- A National Legal Literacy Campaign

To inform victim-survivors, families, schools, and frontline workers about legal rights, processes, and what to expect from the justice system. - National rollout of Independent Legal Representation (ILR) for victim-survivors

To provide victims with their own legal advocate during police investigation and court proceedings: safeguarding privacy, contesting unlawful subpoenas, and offering continuity of care. - Legal process education in schools, universities, and for frontline professionals

To close the knowledge gap before it opens, and equip the next generation with the tools to understand and navigate the legal system.

“We are now teaching consent, but not what comes next,” says Sarah. “Victims walk blindly into a legal process designed to disempower them, and we blame them when they walk away. Essentially, victims are punished for doing what they are told to do – seek justice against their perpetrators.”

Former Victoria Police detective and SAYFE co-founder Jacob Gooden highlights that the justice system’s failures often begin not in the courtroom, but in the very first moments a victim-survivor seeks help.

“The way a victim-survivor is made to feel at their first point of contact with police plays a huge role in whether they choose to continue. One of the most important lessons I learned was that the “stoic, teflon cop” approach is not conducive to positive outcomes for people who come to you in their time of need. It is far better that they see you as a human being who happens to be in a profession capable of helping.”

Senior Solicitor, Victim Advocate and Sexual Violence Specialist Julie Sarkozi says the system was never built for private crimes like sexual violence. “It assumes quick reports, clear evidence, and tidy facts. Victims are often retraumatised by delays, disbelief, and defence strategies that weaponise their medical and counselling records. Even the application for access feels like a violation”.

“With ILR, that changes. You finally have client-legal privilege. You have someone whose job is to protect your interests. If we could promise people, ‘You’ll be looked after, and you’ll have your own lawyer,’ more victims would come forward. And fewer would be harmed again by the process.”

Consulting victimologist and former SA Commissioner for Victims’ Rights Michael O’Connell agrees, arguing that ILR doesn’t just support victims, it strengthens justice.

“Victims’ rights are portrayed as passive; they exist only if you know to ask for them,” he says. “ILR transforms rights from symbolic guarantees into operational protections.”

“It doesn’t bog cases down; it can actually expedite them. Prosecutors are better informed, charge negotiations are more robust, and proceedings are less likely to be derailed. If we truly believe victims are participants in justice, the remedy is simple: give them a lawyer.”

The report makes it clear that there is not only an information gap but also a systemic and cultural black hole. Fixing it will require a baseline of legal education, early access to rights, and a justice system that acknowledges victim-survivors as participants, not props, in their own pursuit of justice.

If this article has brought up any issues for you, please consider reaching out for support:

1800RESPECT: 1800 737 732

Canberra Rape Crisis Centre: 02 6247 2525

Domestic Violence Crisis Service ACT: 02 6280 0900

Lifeline: 13 11 14